TAI’s Potential Impact on the Tax Base

As transformative AI systems transition into the mainstream economy, they threaten to undermine a fundamental premise upon which modern government finance rests: the taxation of human labor. To understand this threat, we need to distinguish between labor and capital income – and how governments tax each.

Labor income refers to compensation for human work: wages, salaries, and employment benefits. This income is taxed through multiple channels: personal income taxes, payroll taxes, and social security contributions. These taxes are difficult to avoid – wages are reported automatically, deductions are limited, and the tax base is relatively immobile.

Capital income refers to returns on ownership: corporate profits, dividends, capital gains, and interest. This income faces a significantly more fragmented tax regime. Corporate profits are taxed at the business level, then again when distributed as dividends or realized as capital gains. However, capital income benefits from extensive deferral opportunities, deductions, and most importantly, geographic mobility.

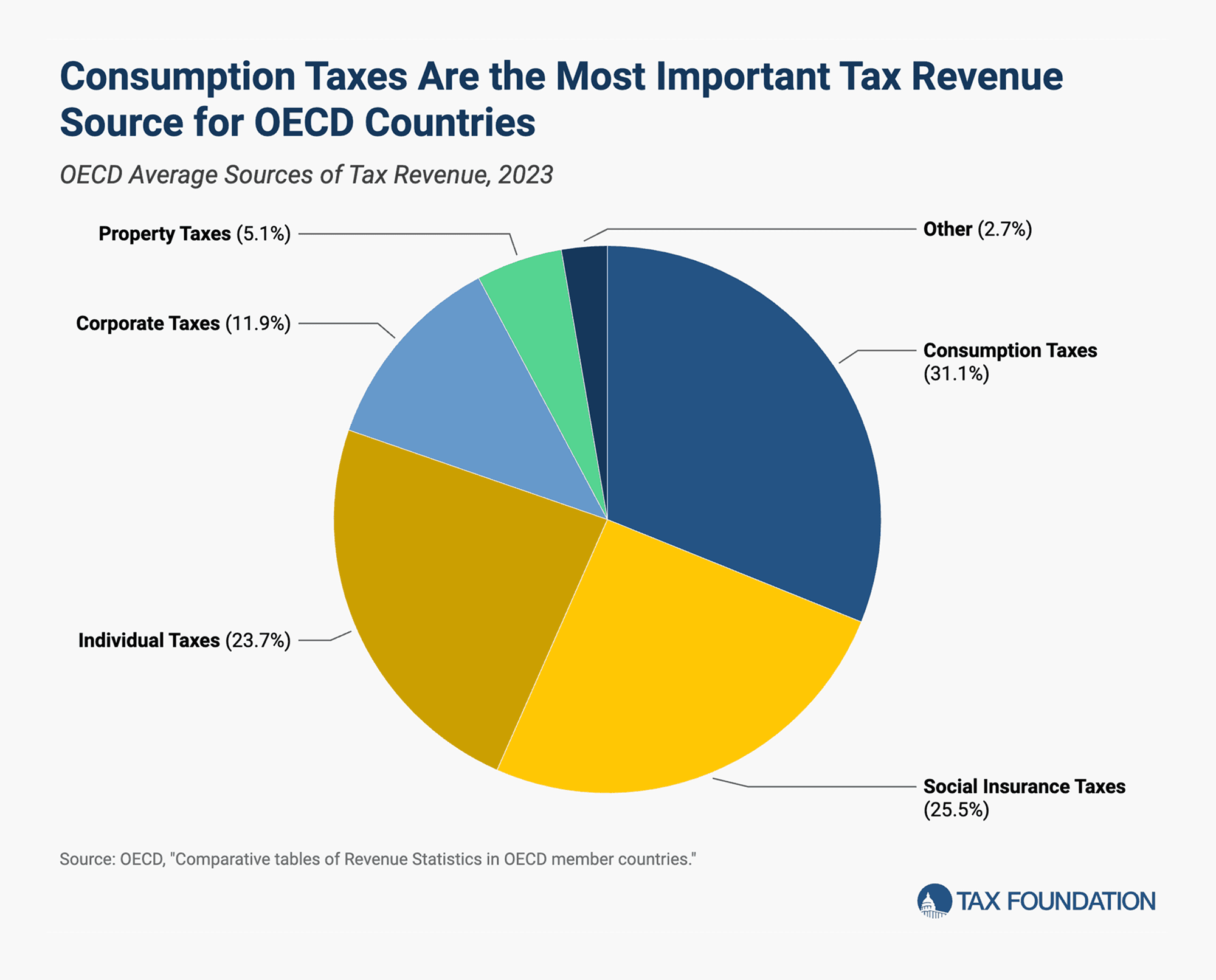

The distinction matters because labor income currently dominates most national tax bases. Around the globe, labor receives 50–70% of total national income. As a result, taxes on labor constitute nearly half of government revenue in developed countries.¹

If TAI replaces a substantial portion of human labor with automated systems, we could see major upheavals in this status quo. We believe the vast majority of countries should be concerned about the potential of falling tax revenues in a world with transformative AI.

Without taxation reform, a shift of economic value from human labor to capital could reduce global tax revenues. Furthermore, a concentration of profits among a small set of highly-automated multinational enterprises could further reduce corporate tax revenues outside of a few AI-leading countries. It’s a nuanced topic – but we think it is clear that national tax experts should be considering the possibility of transformative AI economic scenarios in their long-term tax modeling.²

Let’s discuss two potential key implications of powerful AI on taxation:

Implication #1: Transformative AI could lead to an unprecedented shift from labor to capital income, which could drastically shift the overall tax base.

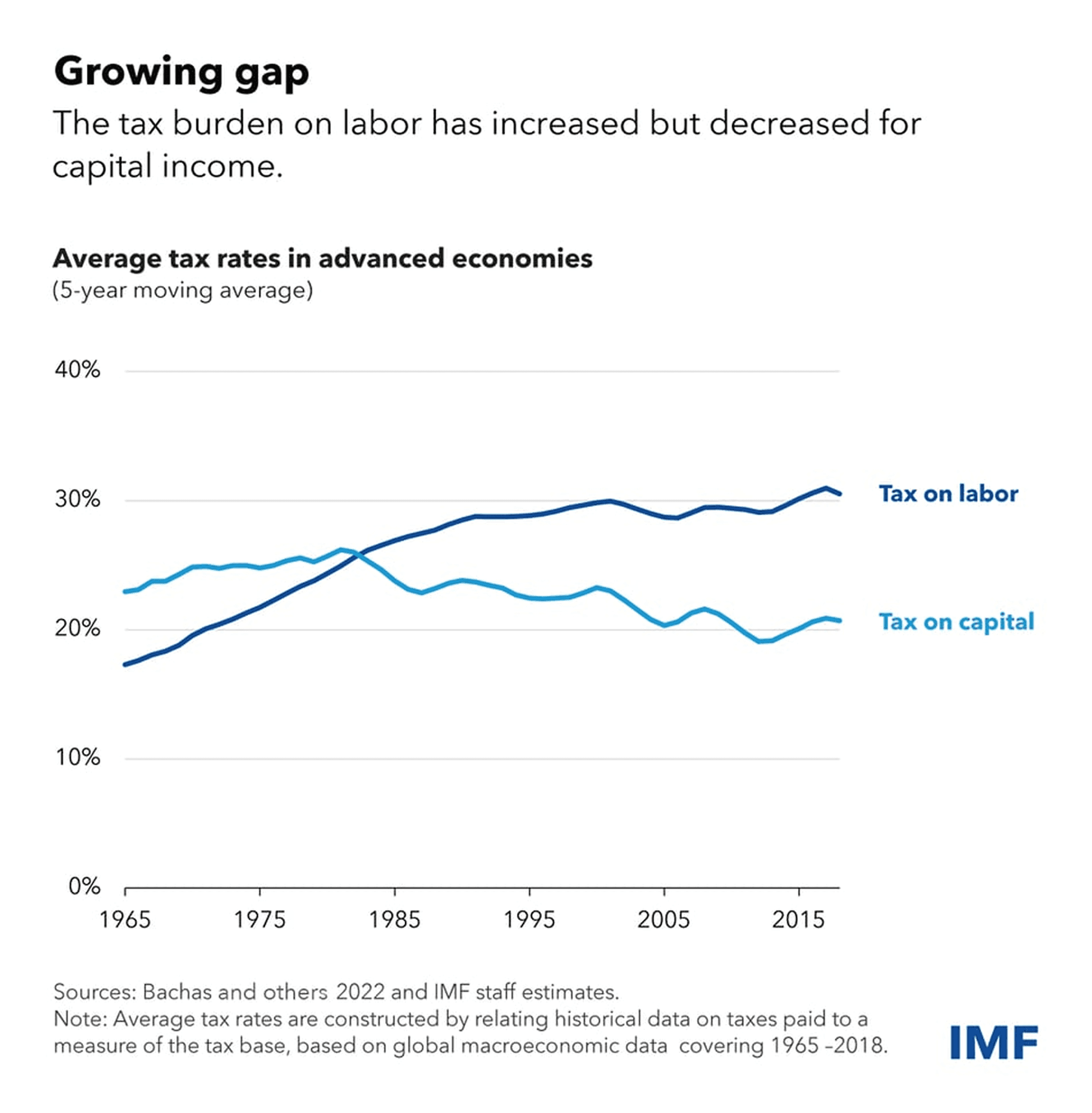

Proponents of near-term TAI are concerned that a rapid shift of many cognitive labor roles to automated systems will lead to an unprecedented drop in the labor share. That share would be captured instead by capital, via higher corporate profits and capital gains accruing to the owners of AI systems. This could have a massive impact on national tax bases, because of the relative tax rates on labor vs. capital income today.

Labor income today faces comprehensive taxation. The average tax wedge on labor across the OECD is 34.9% – the combined burden of personal income taxes and social insurance contributions as a percentage of total labor costs³.

Capital income – and correspondingly, corporate profits – face substantially lighter taxation. The average statutory corporate tax rate across OECD countries is 20.2%⁴, and large multinationals often pay effective rates below this through various tax planning strategies. Crucially, this 20.2% rate applies only to profits after deducting operational expenses, depreciation, and other costs – not to the gross economic value created, as labor taxes do.

Beyond the initial corporate tax, when profits are distributed to shareholders as dividends or realized as capital gains, they face additional capital taxation. However, these subsequent taxes are often at preferential rates, can be deferred indefinitely, and are easier to avoid through jurisdictional arbitrage than labor taxes.

This disparity can be seen very clearly in the tax revenues of developed countries. With a few rare exceptions, income taxes and social security contributions make up more than 50% of federal revenue in most developed countries. Corporate taxes, by comparison, account for a mere 12%⁵.

Consider a simplified illustration: when a human worker earns $100,000, that compensation generates tax revenue through multiple channels – income tax, employer payroll contributions, employee social security payments. If the exact same economic value is generated by an AI system, only corporate profits are captured immediately, and only after deductions and other write-offs reduce the taxable base. In practice, the effective corporate tax rate becomes even lower than the statutory tax rate.

Of course, there are many complicating economic factors. Labor displacement or wage decreases would lead to further disruption of fiscal revenue. Reduced economic activity from decreasing labor incomes could have many tertiary effects.

On the other hand, AI systems will not replace human labor in a 1:1 fashion. Skyrocketing growth could also counteract tax base challenges. We recommend looking at some recently published detailed economic modeling by RAND on the topic of drops in tax revenue from reduced labor incomes.

Implication #2: Transformative AI could lead to a massive increase in the concentration of profits and economic growth among the largest AI-driven multinational enterprises.

One of the core implications of TAI is that by reducing the need for human labor, AI-driven corporations should be able to rapidly grow and outcompete their more labor-intensive counterparts on speed of execution, prices, and more.

These corporations may see massive economies of scale and first-mover advantages that compound their market dominance: steep barriers to entry (e.g. training frontier models), control over critical resources (e.g. chips and datacenters), and network effects (e.g. low deployment costs).

Waymo is a prominent example: by no longer needing to pay humans, it could soon become cheaper, more available, and more reliable than other taxi services. By solving the operational pipelines of large-scale manufacturing, reliability, and building regulatory trust across thousands of jurisdictions, it may eventually become a leader among only a handful of automated corporations replacing tens of millions of human drivers.

It is possible that the majority of future economic growth across each sector could accrue to a similarly small class of “superstar firms” – perhaps 2 - 10 dominant competitors in every industry. There is some evidence we are already seeing a preliminary version of this growth concentration in today’s “AI bubble”.

The first tax challenge this exacerbates is that the largest digital multinational enterprises (MNEs) are still being taxed substantially below the 20.2% OECD average statutory rate. These corporations are experts at reducing their effective tax rates via creative but legal strategies such as profit-shifting, tax havens, and transfer pricing.

About a decade ago, this problem was actually much worse. For a period of time, corporations like Apple were able to get away with paying essentially zero corporate taxes on billions in profits, via clever loopholes such as the “Double Irish”. Today, Apple and Google both are paying roughly 15.6% in effective corporate tax rates globally – below the 20.2% headline rate, but significantly more than before.

The second tax challenge this exacerbates is that the distribution of these taxes on digital MNEs is often largely skewed towards a small subset of countries. For example, Google pays over 80% of its corporate taxes in the US, even though the US generates less than 50% of its revenue. Some may consider this fair, as the US is the “tax residence” of Google and therefore deserves a larger proportion of corporate profits. In practice, it means that Google contributes vanishingly little in corporate tax revenue to most other countries where it operates.

What this means is that highly automated, multinational “superstar firms” would cause even greater strain on a global taxation regime already struggling to properly account for today’s digital MNEs. AI-driven powerhouses like OpenAI may similarly contribute only 15% in corporate profit taxes, largely to the US government at the exclusion of other countries. This could be catastrophic in scenarios where such “superstar firms” capture an ever-increasing proportion of global economic growth and profits, while only needing thousands of employees in a few AI-leading countries.

One Solution: A Progressive Global Corporate Tax

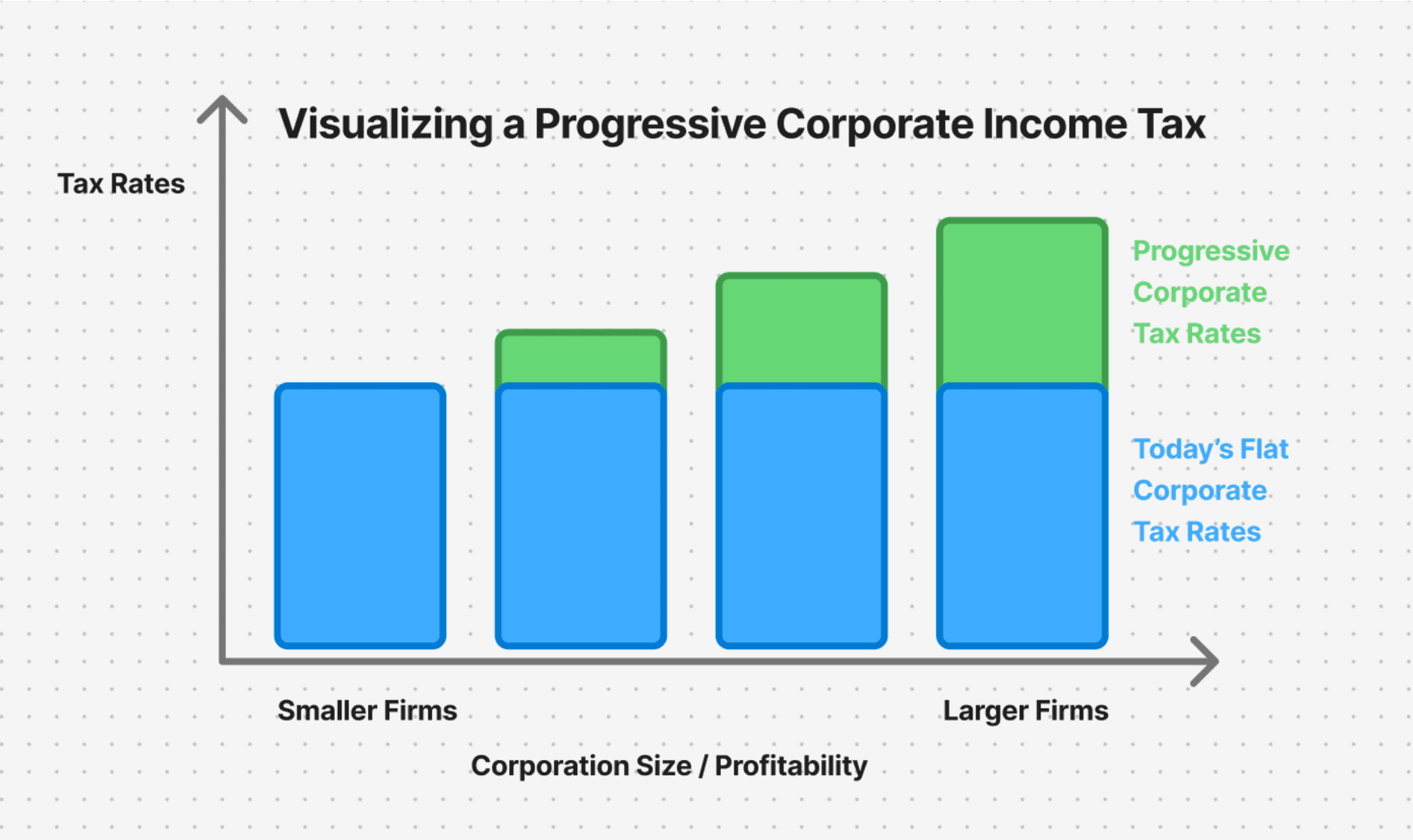

There are a wide variety of plausible taxation responses to the challenges described above. In this piece, we’ll propose just one for thought. A well-enforced progressive global corporate tax would directly counteract tax base erosion from both a shift from labor to capital, and a concentration of profits among the largest MNEs.

Today, most national corporate taxes are flat: nearly all companies within a jurisdiction pay roughly the same percentage of their profits, no matter their size.⁶ A progressive corporate profit tax simply means that the largest and most profitable firms should pay a higher rate of taxes on their profits, as is the case with progressive income taxes globally.⁷ The most familiar approach is profit-based progressivity, in which firms move through higher rate brackets as their net profits increase. For example, if OpenAI earns $100 billion in net income, it could presumably pay 30+% in corporate taxes, as compared to a mom-and-pop business paying the default 20%.

Furthermore, national corporate tax rates have strong incentives to remain low because capital is highly mobile. and profits can be offshored to countries with lower tax rates. A well-enforced global mechanism would prevent progressive taxation from exacerbating profit-shifting.

Such a progressive global corporate tax would directly counteract the two primary tax base challenges described above: a shift from labor to capital, and a concentration of profits among the largest MNEs.

It could do this via the following effects:

It could increase the overall rate of taxation on profits derived from capital rather than labor, potentially restabilizing tax bases worldwide in TAI scenarios.

It could increase the proportion of taxes paid by the largest and most profitable corporations, while not impacting smaller or less profitable firms. The vast majority of firms and workers would be unaffected by a well-designed progressive corporate tax.

In short, such a policy is conceptually well designed for exactly the economic scenario we are describing above due to TAI.

This proposal aligns with the strategy of capturing economic rents, which has broad support among economists. It is theoretically most efficient to tax supernormal profits, or profits beyond those useful to continue operations or reinvest in further growth. In TAI scenarios, superstar firms would likely be capturing massive amounts of economic rents, as they generate profits well beyond normal returns that accrue to a smaller and smaller subset of people.

Philosophically, this also has solid underpinnings. Most would agree that the largest beneficiaries from AI should contribute proportionally more to the societies that enabled their success. The public investments, collective human knowledge, and digital infrastructure that power AI development should receive fair compensation.

Drawbacks of a Progressive Global Corporate Tax

What would be the conceptual drawbacks of a progressive global corporate tax, as compared to the status quo (flat, low corporate taxes) in most jurisdictions today?

There are a variety of valid responses:

Economists have historically viewed low corporate tax rates and higher personal income taxes to be less distortionary. Corporate taxes are often maligned for creating "double taxation" – profits are taxed once at the corporate level, then again when distributed to shareholders. Excessive distortions could create “deadweight losses”. Despite these criticisms, nearly all economists are aligned that some nonzero level of corporate taxation is efficient and necessary, for reasons beyond the scope of this piece.

Progressive corporate taxation could encourage tax fragmentation. Corporations would be strongly incentivized to split themselves into smaller legal entities to avoid taxation, which would create complex legal challenges. Highly sophisticated profit-shifting strategies could erode or eliminate the effectiveness of progressive taxation. Leading MNEs would certainly face precedent-setting litigation.

Each of these responses certainly hold value. But – through careful design of the implementation, most of these drawbacks could be mitigated. More generally, they may have reduced relative importance in a world where an ever-increasing proportion of economic growth flows directly to AI capital and bypasses labor.

Finally, it’s crucial to note that this strategy is not a panacea for the tax base challenges surfaced by TAI. A healthy tax base is composed of layers of thoughtful, well designed mechanisms, most of which will need to be rethought for an AI-driven economy. Beyond updating existing mechanisms, other novel ideas may need to be considered, such as:

Higher consumption taxes (Korinek, Lockwood)

Equity stakes in AI corporations (Yelizarova)

Business wealth taxes (Gamage)

Increasing land-value taxes (Convergence Analysis)

How to Implement a Progressive Global Corporate Tax

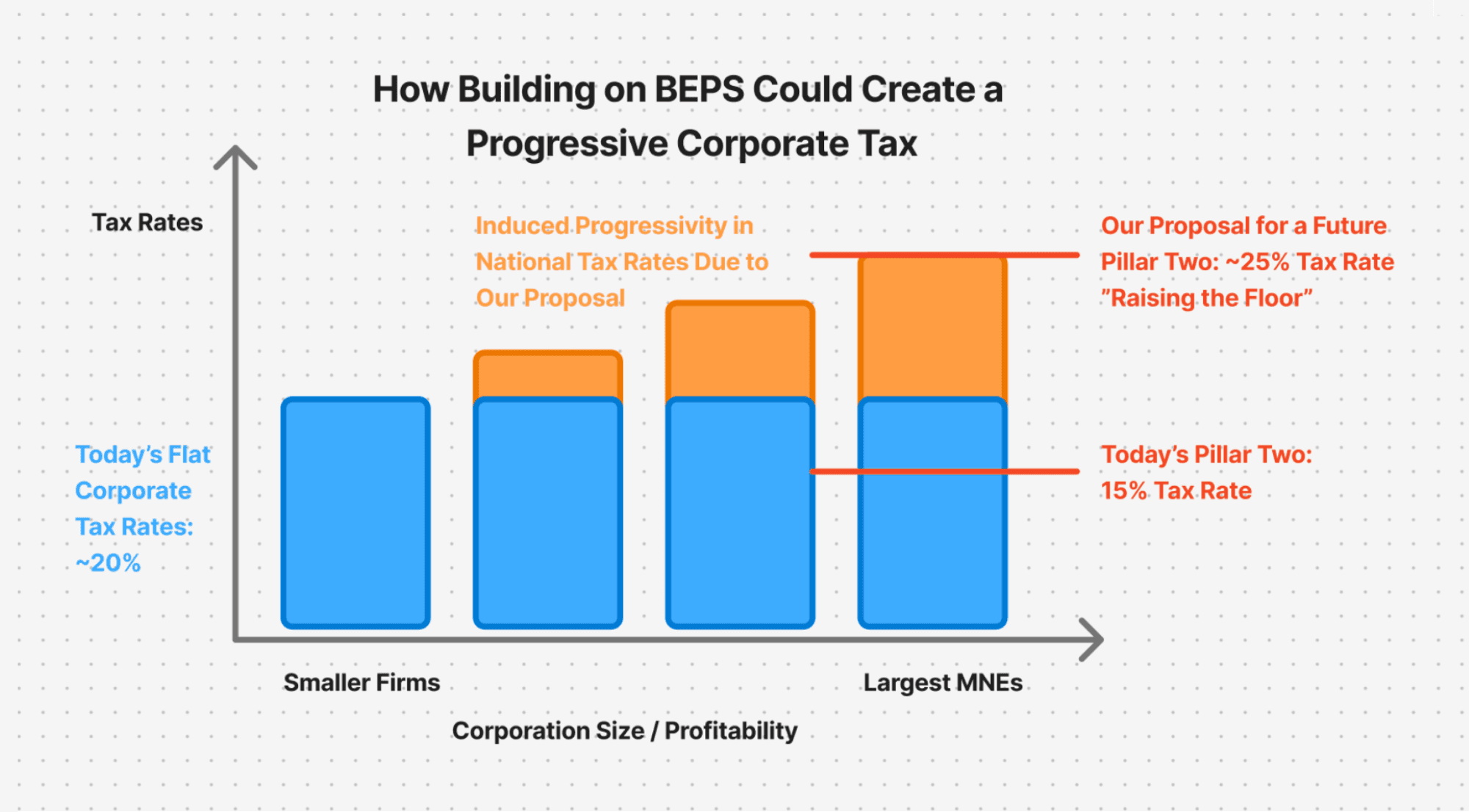

A practical implementation of a progressive global corporate tax would need to engage seriously with international cooperation. We believe the foundations of OECD’s BEPS 2.0 could be leveraged and expanded to eventually “raise the floor” for taxing the most profitable digital MNEs, while allowing individual countries to set their national corporate tax progressivity for less profitable corporations according to domestic priorities.

Summarizing BEPS 2.0

In practice, a progressive corporate income tax enacted unilaterally would likely encourage the largest corporations to offshore their profits to jurisdictions with lower corporate taxation. Today, legal defenses against this form of offshoring are improving, but still quite porous. Academic studies estimate that around 40% of global corporate profits are still being shifted offshore⁸, which is estimated to cost governments between 100 and 240 billion dollars annually⁹.

Notably, the OECD has already made substantial progress towards the most comprehensive global tax base reform in history: the BEPS 2.0 proposal. This project comprises two pillars: Pillar One, which proposes re-allocating taxing rights to jurisdictions where companies receive revenues, and Pillar Two, which proposes a global minimum tax rate.¹⁰

Pillar One: Reallocation of taxing rights to market countries

Traditionally, corporate taxes have been tied to the location of a company’s headquarters or physical presence. With the advent of digital corporations, this has increasingly become obsolete: a company like Google could capture billions in ad revenue from France, but as long as it didn’t have a significant physical presence, it could pay France zero in corporate taxes.

For the largest MNEs, Pillar One partially remedies this by mandating that 25% of their residual profits (e.g. profit margins > 10%¹¹) must be distributed to the country in which it receives revenue. For example, if 10% of a MNE’s revenue came from France, France would be entitled to tax 10% of one-quarter of that MNE’s residual profits. In essence, Pillar One enables countries to tax a portion of an MNE’s residual profits based on where its customers are based, instead of solely where its profits are booked.

Pillar Two: Setting a global minimum corporate tax rate

Pillar Two seeks to ensure that the largest MNEs (consolidated annual revenue at least €750 million) pay a total effective corporate income tax rate of at least 15%, independent from where they operate. It achieves this through a set of coordinated rules¹² that reassign taxing rights to other jurisdictions when a country chooses not to exercise them, guaranteeing a global 15% minimum tax rate if successfully implemented.

In our opinion, BEPS 2.0 is the most thoughtful and feasible solution for fair global corporate taxation governance today. This perspective is supported by an overwhelming coalition known as the BEPS Inclusive Framework: over 140 countries have previously committed to this reform, including every major economy, the US, and China. However, Pillar One of BEPS is currently stalled primarily due to issues raised by the US, and Pillar Two will now proceed without applying to American MNEs.¹³ Geopolitical conditions may need to shift before BEPS 2.0 could be fully implemented.

Building on BEPS 2.0

It’s exceedingly clear to us that any plausible global corporate tax proposal must leverage the work previously done by BEPS 2.0. In this piece, we’ll describe an implementation strategy where a future BEPS project (e.g. BEPS 3.0) acts as the top rungs of a global corporate tax ladder.

Our proposal would set the rules and rates for multinational firms at the very top – those with the highest profits and global reach. Each country could then fill in the lower rungs of a progressive tax according to their domestic priorities.

In this approach, the BEPS Inclusive Framework would continue to set the minimum taxation requirements for the most profitable and largest digital MNEs globally, as it already does with Pillar One and Two. However, as economic scenarios shift the Overton window, it would gradually evolve to raise taxation rates on the most profitable global firms.

Eventually, the tax rates on these top performers would surpass the corporate tax rates of individual countries. In practice, this would result in a progressive corporate tax. Smaller, less profitable companies would be taxed according to a local (national level) set of regulations. The larger, profitable global firms would be taxed more, according to rules set globally by the BEPS Inclusive Framework.

Over time, nations may have incentives to create further progressivity in their corporate tax rates in order to align with BEPS and avoid “cliff-edges”. They might update their tax code so intermediate-sized corporations pay higher rates than their current flat corporate tax rates, but lower rates than the “top rung” as set by the BEPS Inclusive Framework.

Crucially, each nation would retain full autonomy over how to structure tax rates for corporations that fall below the BEPS threshold – which would be the vast majority of businesses. This would preserve national sovereignty over the vast majority of domestic businesses and protect local firms, while still forcing the largest multinational corporations to be held accountable on a global scale.

Implementing this strategy would require changes to BEPS that are straightforward in concept but politically challenging to enact:

Policy Modification (Pillar 1): Higher share of residual profit for market jurisdictions

Under the current Pillar One design, only 25% of residual profits is reallocated to market jurisdictions. This is a reasonable and modest baseline – but it may not be enough to respond to TAI scenarios.

We suggest that in a future where economic growth becomes massively concentrated to few capital owners in a small set of developed countries, a greater share of economic rents may need to be distributed globally based on proportion of consumption.

We propose that policymakers aligned with BEPS could gradually increase the share of residual profit allocated to market jurisdictions from the most profitable companies. Increasing this rate from 25% to 30%, 40%, or even 50% would better counteract the economic power concentration we expect from TAI and ensure the economic gains from AI are distributed to a wider range of jurisdictions.

Crucially, this would not affect the total amount of taxes collected – it would simply diversify the jurisdictions to which the profits flow.

Policy Modification (Pillar 2): Higher global minimum tax rate

Pillar Two is a landmark in global tax cooperation, but its 15% minimum rate for the largest and most profitable MNEs reflects political compromise more than economic logic. It sits well below the OECD average of about 20.2% for all firms, and beneath the levels in most major economies. As a result, it acts as a global floor – serving as the minimum viable taxation rate for global firms.

In this progressive taxation strategy, we propose inverting this logic on its head. Pillar Two could serve not just as a global floor, but to raise the top rung of the corporate tax ladder – serving as an anchor point for the optimal level of taxation on the largest and most profitable global corporations. Raising this “anchor point” above the default rate of most countries would not only strengthen their revenue bases, but also eventually make BEPS a powerful enabler of more progressive corporate taxation at the domestic level.

The OECD recently estimated that raising the global minimum tax to the 15% rate proposed in Pillar Two would raise an additional $155 - $190 billion in yearly revenue.¹⁵ Further raising this global rate – perhaps to 25% – would capture several times more, as the majority of countries currently have effective corporate tax rates in the 15-25% range and would be directly impacted. A ballpark estimate might suggest a minimum of $400 billion in additional yearly tax revenue.¹⁶ For comparison, recent studies have estimated that developing countries need around $500 billion annually to address climate change challenges.¹⁷

Addressing Feasibility Concerns

Every tax policy expert who has spent time working with the BEPS Inclusive Framework will have deep skepticism about the plausibility of this proposal, and rightfully so.

In the short term, this iteration of BEPS 2.0 is already stalling out due to non-participation from the Trump administration.

On a high level, competing nationalistic incentives make it extraordinarily difficult to secure global cooperation, especially when negotiations over taxing rights often seem zero-sum in nature.

Proposing higher values on rates that are already the result of political compromises can seem divorced from reality.

To this valid pushback, we’ll offer two thoughts:

First, TAI economic scenarios will not happen overnight. This is a long-term strategy, not a gameplan for 2026. Economic impacts and global coordination take years to manifest and synchronize on. Democratic countries can change direction with alarming regularity, and the political reality now may not be the same in four years. In 2024, the BEPS Inclusive Framework was significantly more likely to see widespread implementation with the support of the Biden administration.

Second – in periods of significant upheaval, new ideas and strategies rapidly enter the Overton window. The end of WW2 brought about the creation of the Bretton Woods system. COVID led to countries around the world experimenting with (and with notable successes) previously politically inconceivable ideas, such as direct payments to citizens or child tax credits.

If a significant recession appears driven by AI in the next decade, or an economic crisis proportional to the suggested impact of TAI materializes, it is entirely possible that the economic consensus could shift towards more radical proposals.

The vision of a strong, well-enforced global tax system that fairly captures the economic rents from massively profitable AI corporations may seem beyond the pale today. But - it’s critically important to prepare for potential scenarios and have policy responses ready to discuss and reach for in case they arise.

Let us navigate this upcoming transition with thoughtfully designed policies, strong global coordination, and a commitment to economic prosperity for all.

Thanks to Andrey Fradkin, Yolanda Lannquist, Michael Mills, Carter Price, David Gamage, Darien Shanske, Trish Ieong, Anna Yelizarova, and Tom Mulligan for their feedback on this piece.